It is hard to imagine in this era when military strategists talk of robot warfare and satellites fighting in space that not all that long ago mounted cavalry, men on horseback, was still regarded as an essential part of any fighting force.

But it was not just armies that moved by old-fashioned horsepower. Everything from milk to meat that wasn’t on the rails came on a well-shod horse. And one of the largest producers of horse shoes in America and the world was the Bryden Horse Shoe Company of Catasauqua. As with many things in the Iron Borough in those days, David Thomas had a role.

David Thomas

As an immigrant from Wales, Thomas had come to America with his family at the urging of Lehigh Canal founders Josiah White and Erskine Hazard. Thomas had worked in England for George Crane’s iron furnace there. On July 4, 1840, Thomas fired up what became the first commercially successful anthracite coal iron furnace in America. That sparked an iron furnace building boom across the Lehigh Valley and America. His sons followed in his wake, creating the Thomas Iron Company.

According to one source it was Thomas in 1879 who urged a friend, Oliver Williams of Connecticut, to come to Catasauqua to set up the Catasauqua Manufacturing Company rolling mills of which Williams was to be president.

Williams, with his partners William Hopkins and Joshua Hunt, began to look around for iron products that he might find profitable. The economy was beginning to revive from the Panic of 1873 and investors were looking around for business opportunities.

On October 11, 1882, the Allentown Democrat newspaper announced its arrival in the Iron Borough: “Horse Shoe Factory at Catasauqua,” the headline read. Machinery was already being put into place. Williams decided on a new process of making horse shoes created by George Bryden of Hartford, Connecticut, would be just the thing, and he purchased the patents from him.

“Under Bryden’s process,” notes one source, “the shoes were completely formed under the blows of a heavy hammer, whereas other shoes were rolled and the heel and toe-caulks welded by a blacksmith.” With that the Bryden Horse Shoe Company, as it was officially called, was born.

This process could apparently produce horse shoes at a faster rate and fit better than the older process. With $60,000 in capital Willams erected a one-story brick building on the northwest corner of Railroad and Strawberry Alleys. By 1888 business was so good, an expansion was needed. Land was purchased along the west side of Front Street over into what later would become North Catasauqua.

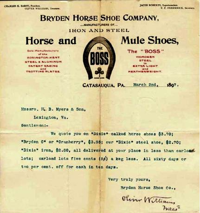

Bryden Horse Shoe Company

One of the real driving forces behind the development was Jacob Roberts, part owner and part superintendent of the Phoenix Horse Shoe Company of Poughkeepsie, New York. Roberts built and equipped the plant and had a complete operation from rolling mill plus bending and pressing irons designed exclusively for manufacturing horse and mule shoes. Longfellow’s village blacksmith “could stand under the spreading chestnut tree,” hammering horseshoes “with his large and sinewy hands,” as the old poem had it, but the Bryden Horse Shoe Company was turning them out by the barrel full.

It was of course one thing to turn out a lot of horse shoes, it was another thing to sell them. And Bryden did not lack competition. Williams discovered just the man in George Holton. An ambitious Englishman, Holton was originally working with the Davies and Thomas company on a tunnel project in Hoboken. His knowledge of the iron industry was extensive.

Williams spotted in him just the right personality to be a super salesman. Traveling nationwide like Harold Hill in the Music Man, Holton “drummed” his way through small towns and big cities for Bryden Horse Shoes and got to know the territory. He set up agencies wherever he went, securing orders. And eventually it was under Holton’s direction that Bryden hit the international market.

The British Empire was having some trouble with a little “dust up” down in South Africa that history has come to call the Boer War, beginning in 1899. The Boers were a group of Dutch origin farmers on the tip of the continent. This required a lot of horse and mule flesh and Holton being of British ancestry probably didn’t hurt his salesmanship any. Soon a weekly train-car load of Bryden horse and mule shoes was making the long route across the Atlantic to take on the rebellious subjects.

History tells us that the Boer War was far from a walkover for Britain. Some sources attribute its eventual success to the use of mounted infantry, infantry who rode horses instead of marching. And at least some of them were on horses shod with shoes from the Bryden Horse Shoe Company. Among the other customers at the time were Czarist Russia’s Cossack units and Berlin’s horse drawn streetcars.

Sales slip from Bryden Horse Shoe Company

Whatever else it did, the Boer War brought full employment to Bryden. To judge from photos of the period many of them ranged from young men to boys. It was then one of the largest industrial employers in the Lehigh Valley, with 500 employees. Holton married Williams’ youngest daughter Jessica. Williams died in 1904. Holton then became president until his death in 1913. Then it was taken over by his wife as the company’s president.

In July of 1914 Bryden, along with the rest of Catasauqua, celebrated its Old Home Week parade. Unfortunately, rain fell on that day, but the next day’s newspaper headlines were upbeat. “RAIN FAILS TO MAR CATASAUQUA’S HOMECOMING PARADE, noted one. On the corner of another was a small article about the death by assassination of an Austrian archduke and his wife in some far away place called Bosnia. “An archduke more or less really doesn’t make that much of a difference,” commented one out of state editor.

But by that August all the major nations of Europe were at war. Most of them maintained mounted cavalry units as a part of their military. But technology that included the machine gun and later the tank was about to change all that. A year later the trench lines had frozen the conflict into stalemate. “War, which once had been cruel and magnificent had become cruel and squalid,” Winston Churchill, who as a young man took part in cavalry charges was later to write.

At roughly the same time the gasoline powered engine was gradually ending the reign of the horse drawn carriage and delivery wagon.

In 1917 the business and property were sold to the Never Slip Co. of New Brunswick, New Jersey. Later it was absorbed by the Phoenix Horses Soe Company of Poughkeepsie, New York. By 1928 it and several other horse shoe related businesses became the Phoenix Manufacturing Company and in 1939 closed its rolling mills for good.

Historical marker for Bryden Horse Shoe company

It survives under a few other names. “Today,” notes one source, “as the Phoenix Forging Company of Catasauqua it continues to modernize, manufacturing forged fittings for pressure vessels.”